My earliest moon photographs, shot on film, were planned using astronomical prediction tables, a large map, a protractor and a compass. And although I usually ended up in the right place at the right time, the preparation was arduous––even tedious. Then one day a photographer friend told me about Photoephemeris.Com/Web, an online application that I could use to plug in locations and dates to find everything I needed about the moon and sun’s appearances above the horizon—anytime and anywhere on earth.

Since that time, over ten years ago, Stephen Trainor has greatly improved his already excellent application. I will demonstrate several methods to use the app to predict and plan for photographing the full moon during a Zoom class this March, 2021. (Date and time to be decided) The presentation will also include valuable tips on exposure and equipment, with time for group questions and discussion. The link for registrations will be announced shortly in an upcoming Marty Knapp News email. Compliments of Mr. Trainor, registrants will receive a 40% discount coupon code for subscription to the Pro Version of the application. As far as I’m concerned, the Pro version is indispensable!

To be alerted to the details of this event, please contact me at classes@martyknapp.com. In the meantime check out the examples I made for a recent moonrise prediction and photograph using the Photo Ephemeris web app.

Five Steps to Successful Planning of a Full Moon Photograph

Click on images for larger renderings

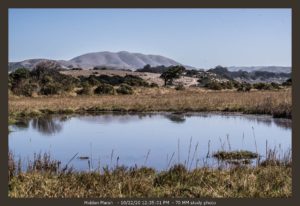

1. Make a daytime study photograph of target location:

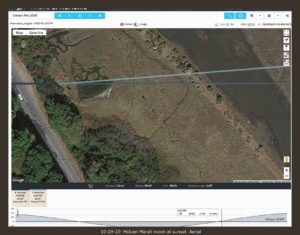

2. In Photo Ephemeris, satellite view, verify location:

3. In Photo Ephemeris, topo map, check bearings, elevation of moonrise:

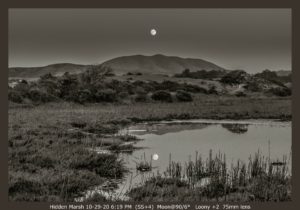

4. Create prediction photo using data obtained from Photo Ephemeris:

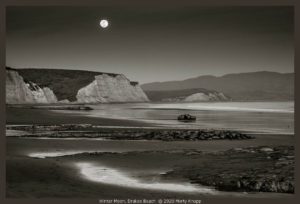

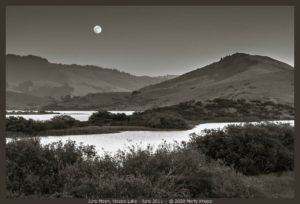

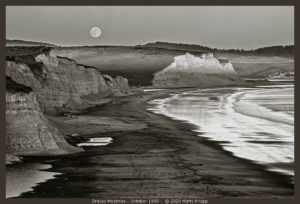

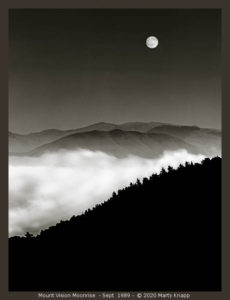

5. Arrive at destination on date & time selected to photograph the moon!