“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s

not the same river and he’s not the same man.”

–Heraclitus, Greek philosopher, circa 6th c. B.C.

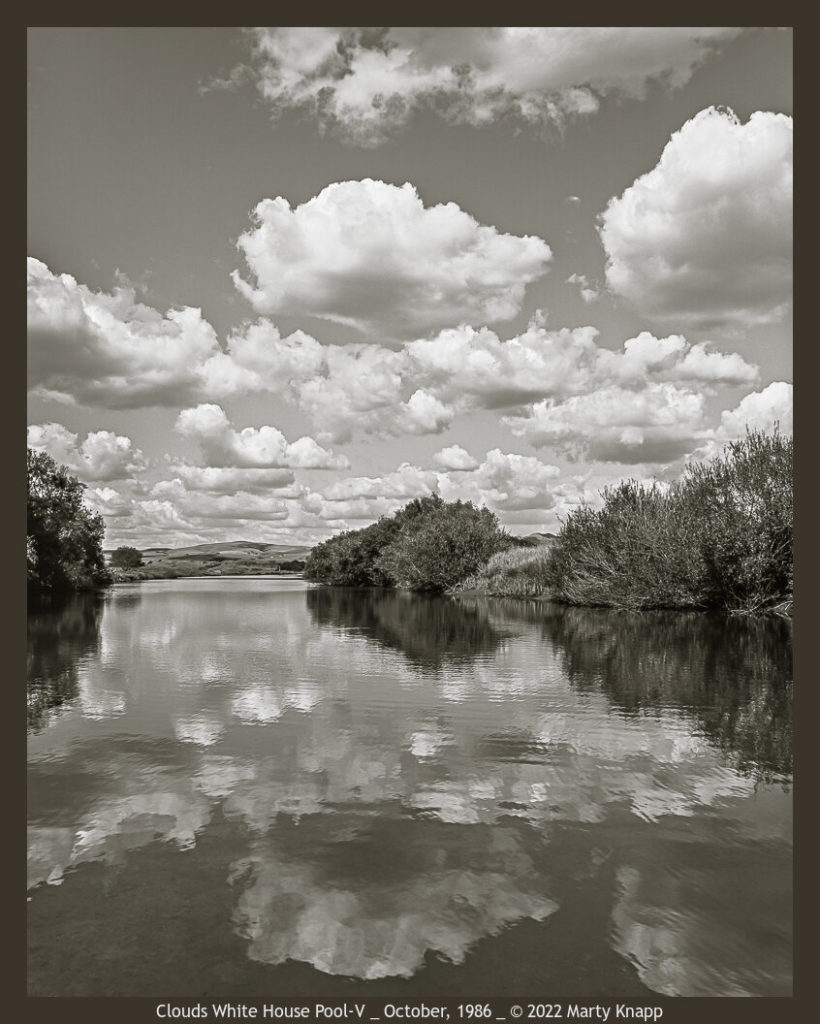

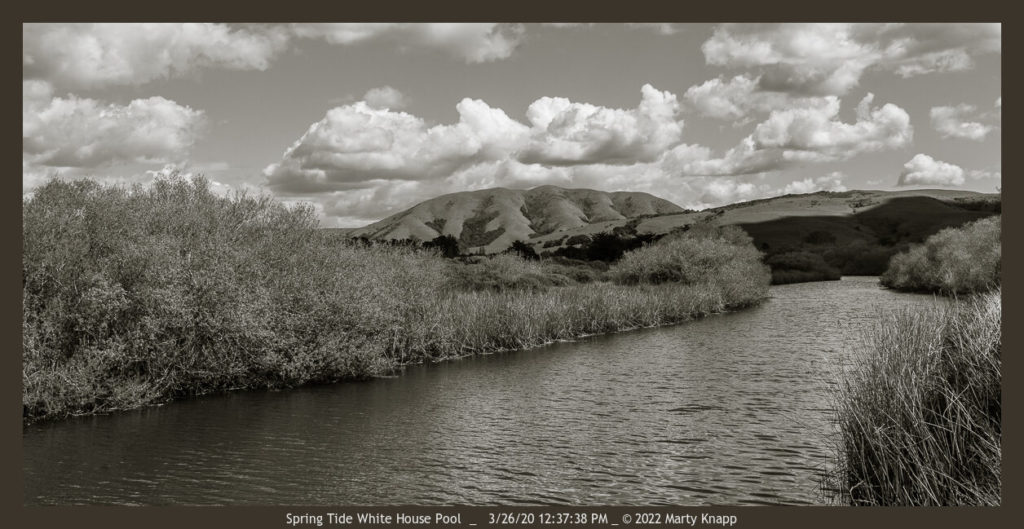

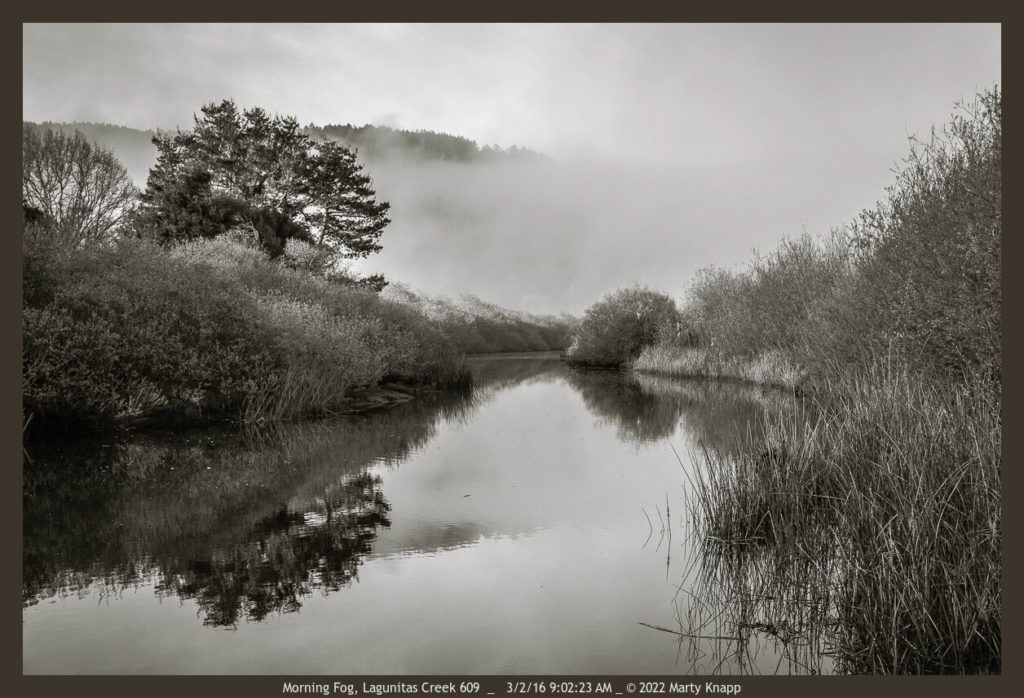

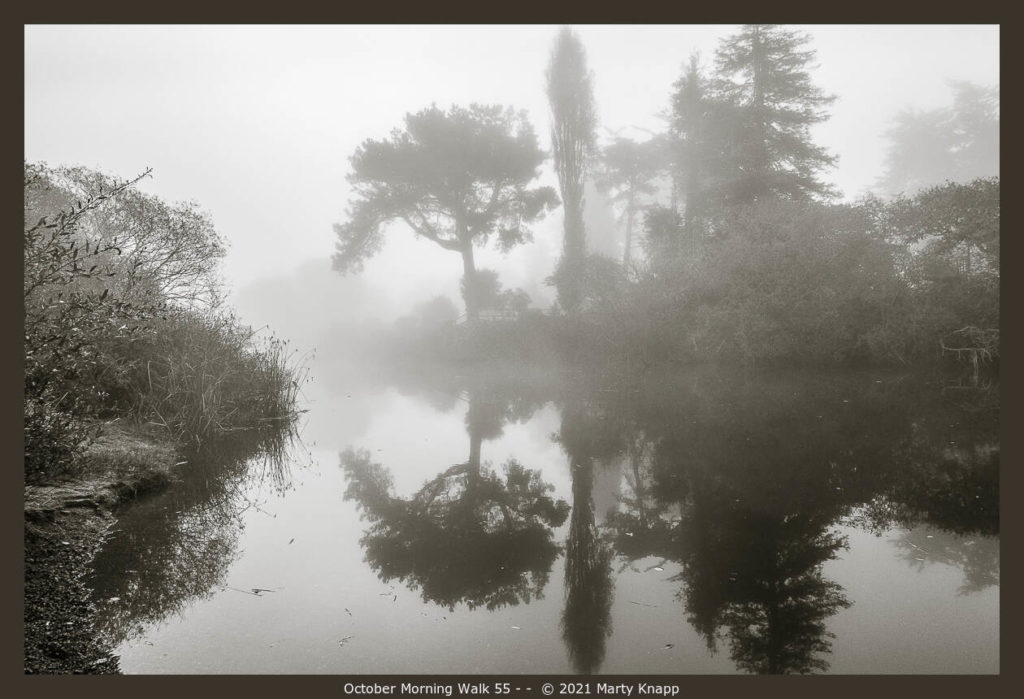

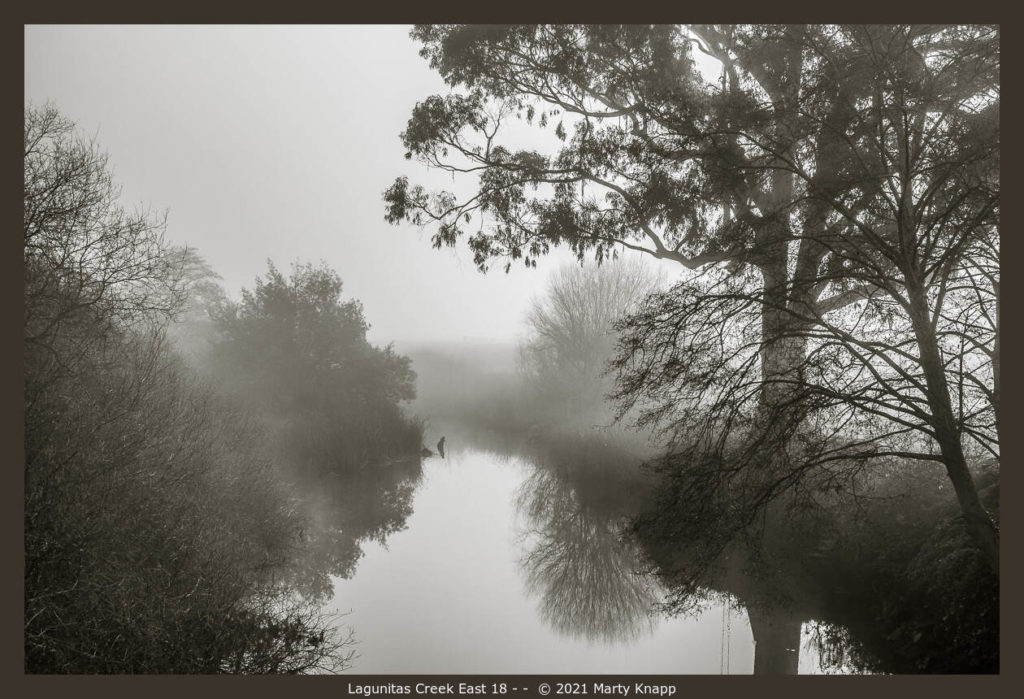

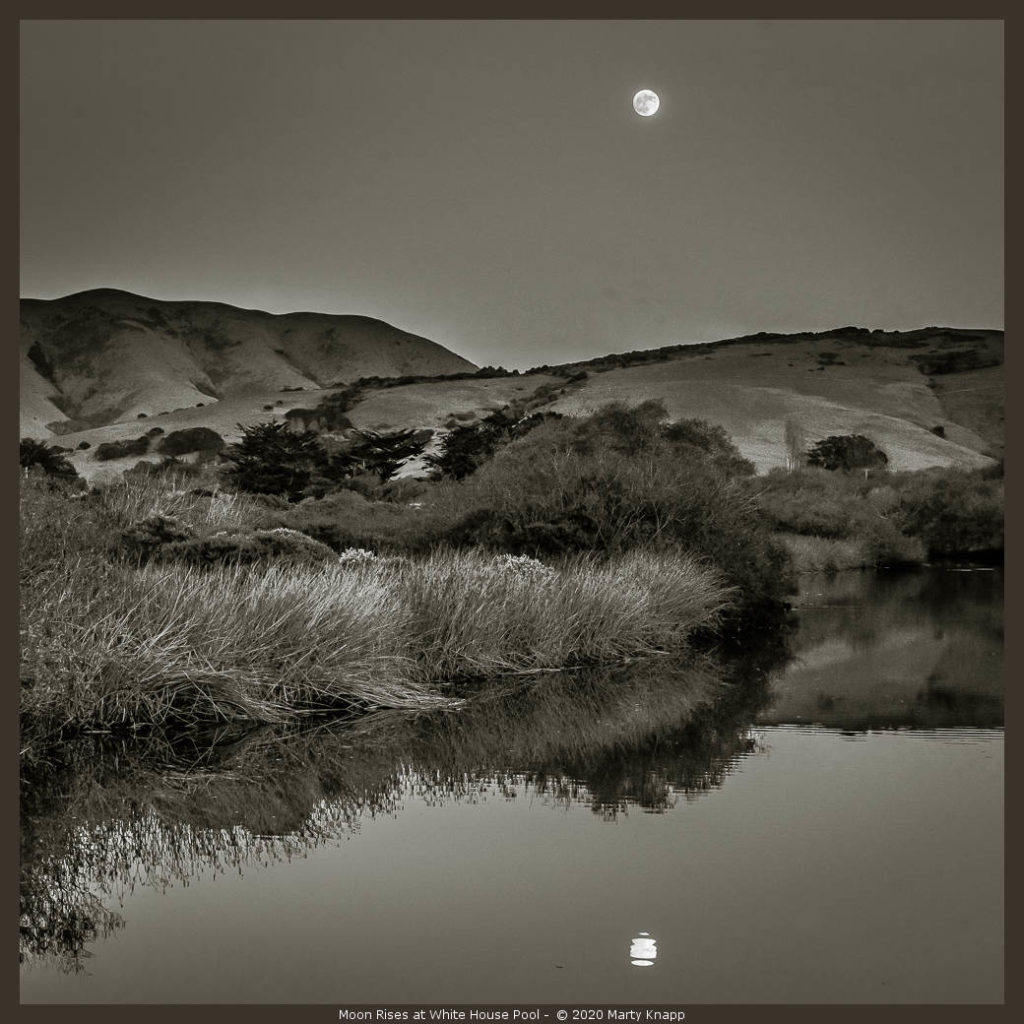

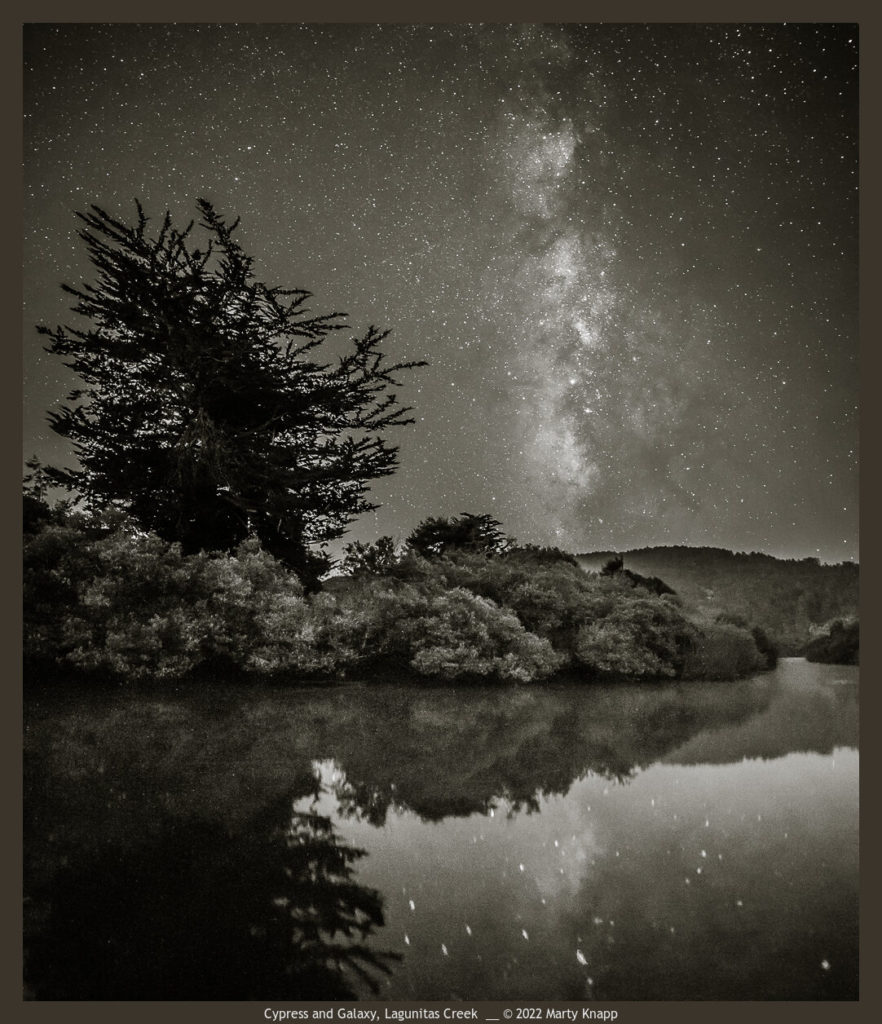

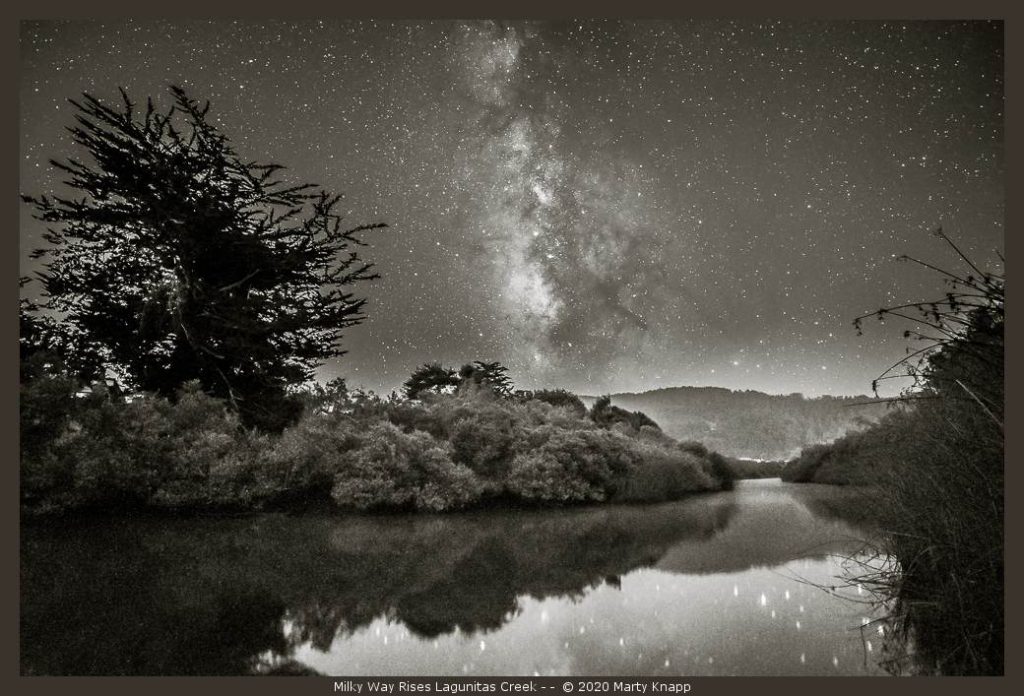

In my case, I did not “step into” the same river twice, because both the river and I have changed. I have photographed Lagunitas Creek for more than 30 years. The river changed each time–with the seasons, the weather and the hour of day. I too am different, tempered by what I saw. I was drawn first by the spectacular light I found there. Later, I was seduced by the mystery of fog-dampened shapes along the banks, and, most recently I stood in awe at the water’s edge when the moon shone or stars reflected on the still waters. What follows are the highlights, in pictures, of my thirty-year journey along Lagunitas Creek.

Lagunitas Creek is also known as Papermill Creek. On maps it’s always spelled Lagunitas, but the locals have long called this beautiful channel Papermill Creek, named for the Pioneer Paper Mill that produced its products adjacent to the creek in Lagunitas from 1856 – 1915. I have used both names in the titles of my photographs.

Lagunitas Creek courses some 24 miles through west Marin county. The creek’s headwaters are on the northern slope of Mount Tamalpais. The stream steps down, passing through several reservoir lakes, eventually winding through the Samuel P Taylor redwoods park. From there it passes just west of Point Reyes Station before turning north to empty into Tomales Bay at Inverness.

Just south of town it flows under The Green Bridge, an old steel bridge spanning Highway One. Then it courses gently though the wetlands of Point Reyes as it heads toward a bend in the creek known as White House Pool. It is at these two places, near my home, the Green Bridge/Wetlands and White House Pool that I have created my most memorable creekside photographs.

These favored nearby places have provided many distinctly different views and moods. I am grateful to live in such a visually rich natural environment and to have access to the ever-changing beauty that surrounds us here.

Scroll down for some more photographs I’ve made at Lagunitas Creek during the last 30+ years. As with all photographs on this site, prints and framed editions in varying sizes may be ordered online. They are cataloged here: Lagunitas Creek Collection.